Distributed Energy Resources (DER) are slowly and irreversibly changing how our energy grid functions. Yet many people don't know what Distributed Energy Generation (DEG).

The Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy defines DEG as, "When electricity is generated from resources, often renewable energy sources, near the point of use instead of centralized generation sources from power plants."

This sounds simple enough, but the shift is forcing the utility industry to completely reinvent itself. This transformation is affecting energy companies, the environment, consumers...basically everyone. So let's dive in and see what Distributed Energy Generation really is, and what it means.

Out With the Old - How the Utility Monopoly Arose

Traditionally, energy has been created at one, central location. A single, massive power plant produces large quantities of energy. That electrical energy is then distributed from the point of origin to the businesses and residences that it serves.

This is the energy distribution model that most people are familiar with. It is what has been used for decades. Traditional power plants burn coal or fossil fuels, harness hydropower or nuclear power. Constructing these plants takes an enormous amount of money and resources, resulting in a business model where large plants supply vast areas with power. Small, local power plants are not an economically viable option, as large fixed-costs make them disproportionately expensive. This is why power companies send electrical energy through hundreds of miles of power lines to service remote areas rather than creating a local power plant.

Our energy grid was not always set up like this. When humanity was first beginning to use electricity in our daily lives, power companies were in direct competition with each other. They serviced the same areas, which meant electricity functioned similar to cable, in that the consumer could choose their electrical provider. This forced companies to keep their rates and offerings competitive.

This lasted until the Great Depression, during which many utility companies were forced to close their doors. The United States responded by investing in massive energy projects, the Hoover Dam being one of them, to improve public welfare. With the government's involvement, energy regulations were put in place and different utility companies were assigned different territories. This government regulation of utilities spread throughout the industrial world and brought the period of energy competition to an end. Consumers no longer got to choose who provided their power and utility companies now had the benefits of territorial monopolies.

Without the ability to choose, consumers lost their power over the energy companies. Utilities could do what they wanted, as long as it was within regulation, with a take-it-or-leave-it attitude. For some utilities, the rise of energy monopolies meant customer service was no longer a priority. This caused the relationship between utilities and their customers to become strained.

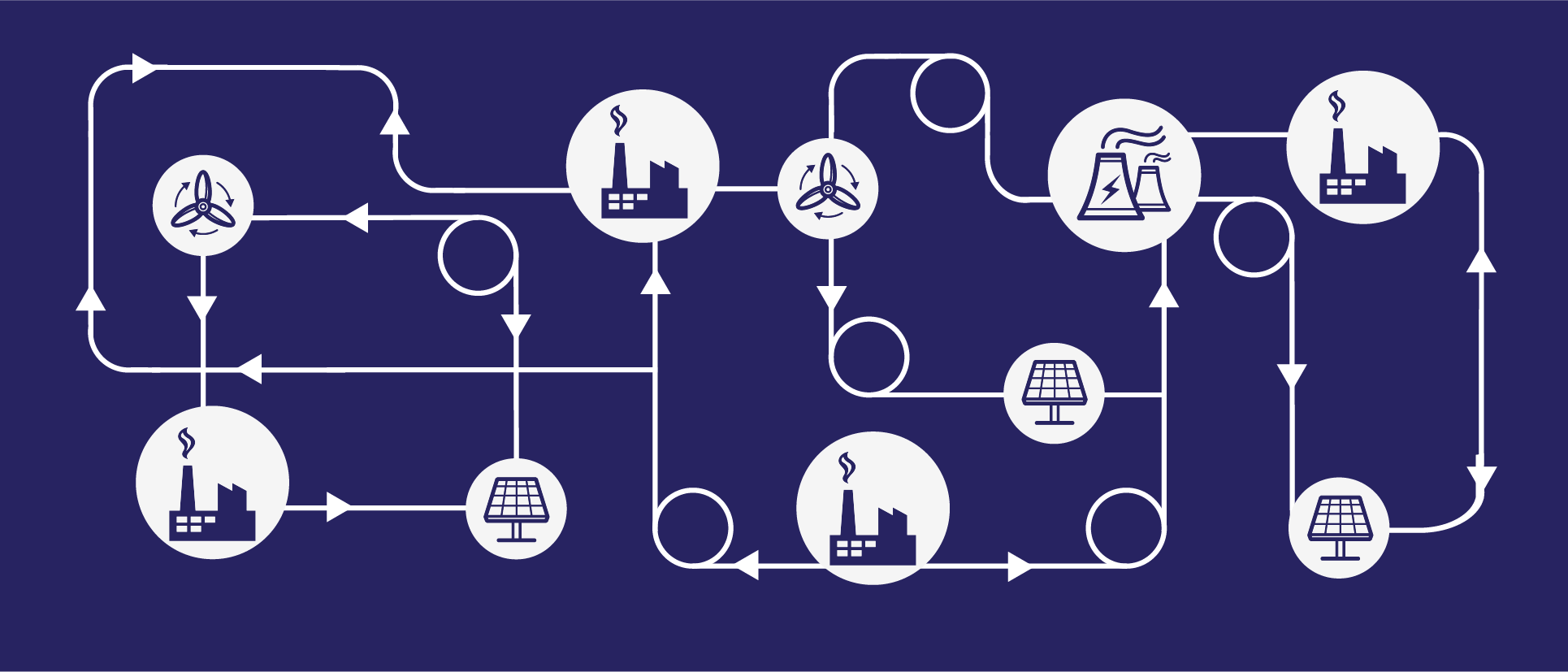

This energy monopoly lasted decades, until technological advances placed energy-generation into the hands of individual consumers. Now customers have a choice: they can buy their energy from a utility, or they can produce it themselves by investing in distributed energy resources and/or building their own microgrid.

Global distributed generation was worth over 57 billion USD in 2017. By 2023, it is expected to have nearly doubled to over 103 billion USD. In 2017 alone, 2,227 MW of residential solar panels were installed in the United States. With enormous numbers of customers choosing to produce their own energy, it is clear that the energy monopoly is officially at an end.

While the decades-long energy monopoly benefited utilities, it also hurt them. A lack of competition left utility companies behind other industries, which had to compete and evolve in order to survive. The result is that today's utility infrastructure is badly outdated. Good customer service is not a term that most people associate with their utility. The data and technology that has reinvented many other sectors is only beginning to bring the energy sector into the modern era. And, perhaps most dire, is the fact that the effective, rapidly-spreading consumer-first model of business has barely begun to penetrate the utility sector.

Learn more about the state of our aging energy grid, and how technology is helping fix it > >

In With The New - The Power of Choice

Individual companies and residences cannot afford to build a coal or nuclear power plant. However, advances in technology have caused the cost of renewable energy sources–including solar panels, microtubines, and fuel cells–to plummet since the turn of the twenty-first century.

Let's take a closer look at solar panels. From 2010 to 2017, the cost of utility-scale solar plummeted from over $5/watt to $1/watt, while residential solar dropped from $5/watt to $2/watt.

For the first time in history, it is economically feasible for a family to install solar panels and produce their own energy. A university can build microturbines. A hospital can purchase fuel cells.

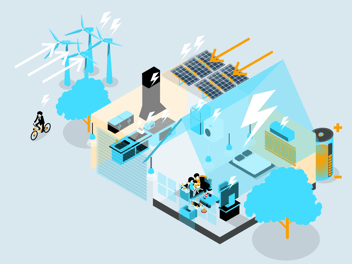

These distributed energy resources can function independently, such as solar panels installed on a single home, or they can form a microgrid. A microgrid is a small energy grid that is tied into a larger power grid, but it can run independently off a local energy source, creating various benefits for consumers.

Now, instead of one power plant servicing 40,000 homes (for example), 200 of those homes may have solar panels that supply part of their power, and another 200 may have formed a microgrid that is mostly autonomous.

Distributed generation, whether from an individual or a microgrid, comes with a lot of benefits. It is faster to build distributed energy resources than a traditional power plant, meaning you can more quickly respond to growing power demand.

Distributed generation can reduce the negative impact of power outages. Since microgrids and individuals who produce their own energy are typically connected to a larger power grid, they can pull power from the grid if the local energy production suffers an outage. This works in reverse, where if the larger energy grid has a power outage, the distributed energy generation source can still function and keep the lights on, so to speak. This can be especially important after hurricanes and other natural disasters.

Distributed generation overcomes the issue of distance. It is difficult for the traditional energy grid to supply remote communities, such as islands or mountainous communities, with power. This is not a problem when power can be produced locally.

Distributed power generation is also more efficient, as energy is not lost during transport and distribution. Only 28-35 percent of fuel consumed by a power plant is ever actually used for power. That number can rise above 50 percent for distributed power generation.

With so many possible benefits, the reasons for switching to distributed generation vary by use case. A business could install generators to reduce peak electricity demand, a family could purchase solar panels to save money, or a grocery store could invest in distributed generation to avoid monetary losses in the case of an outage.

It's important to note that distributed generation is not all new. Backup generators have been around for decades and still make up a large portion of distributed generation resources.

Posted by PDI Marketing Team

Pacific Data Integrators Offers Unique Data Solutions Leveraging AI/ML, Large Language Models (Open AI: GPT-4, Meta: Llama2, Databricks: Dolly), Cloud, Data Management and Analytics Technologies, Helping Leading Organizations Solve Their Critical Business Challenges, Drive Data Driven Insights, Improve Decision-Making, and Achieve Business Objectives.